You can download and explore a hosted version of the notebook here..

Also, please note, the interactive lonboard maps are not displayed on this site.

In this notebook we’ll use the lonboard library to visualize Germany’s population data, which consists of approximately 3 million polygons. By the end, you’ll know how to create interactive maps of large spatial datasets directly in Jupyter notebooks.

Imports

lonboard is designed to work within Jupyter Notebooks. Please make sure you’re working in a Jupyter environment to follow along.

Before starting, make sure you have the following packages installed:

lonboardand its dependencies:anywidget,geopandas,matplotlib,palettable,pandas(which requiresnumpy),pyarrowandshapely.requests: For fetching data.seaborn: For statistical data visualization.

The following modules come standard with Python, so no need for separate installation:

zipfileio

import requests

import zipfile

import io

from lonboard import Map, SolidPolygonLayer

from lonboard.layer_extension import DataFilterExtension

import ipywidgets as widgets

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import geopandas as gpd

import matplotlib as mpl

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from matplotlib.colors import LogNorm

import matplotlib.ticker as mticker

from shapely.geometry import Polygon

import seaborn as snsFetch Population Data

The population data we’ll be using is stored in a .csv file inside a .zip folder. It consists of 100m x 100m grid cells covering the area of Germany, with population counts for each cell. We’ll download this file, extract the data, and load it into a pandas DataFrame.

url = "https://www.zensus2022.de/static/Zensus_Veroeffentlichung/Zensus2022_Bevoelkerungszahl.zip"

target_file = "Zensus2022_Bevoelkerungszahl_100m-Gitter.csv"

response = requests.get(url)

if response.status_code == 200:

with zipfile.ZipFile(io.BytesIO(response.content)) as zip_ref: # Open the ZIP file in memory

if target_file in zip_ref.namelist():

with zip_ref.open(target_file) as csv_file:

df_pop = pd.read_csv(csv_file, delimiter=';')

else:

print(f"{target_file} not found in the ZIP archive.")

else:

print(f"Failed to download file: {response.status_code}")Let’s take a quick look at the first few rows of the data to understand its structure:

df_pop.head()| GITTER_ID_100m | x_mp_100m | y_mp_100m | Einwohner |

|:-------------------------------|------------:|------------:|------------:|

| CRS3035RES100mN2689100E4337000 | 4337050 | 2689150 | 4 |

| CRS3035RES100mN2689100E4341100 | 4341150 | 2689150 | 11 |

| CRS3035RES100mN2690800E4341200 | 4341250 | 2690850 | 4 |

| CRS3035RES100mN2691200E4341200 | 4341250 | 2691250 | 12 |

| CRS3035RES100mN2691300E4341200 | 4341250 | 2691350 | 3 |

While we can’t immediately tell the meaning of each column just from looking at the data, the data description clarifies the following:

GITTER_ID_100m: The unique identifier for each 100m x 100m grid cell.x_mp_100m: The longitude of the cell’s center using the ETRS89-LAEA Europe (EPSG: 3035) coordinate reference system.y_mp_100m: The latitude of the cell’s center using the ETRS89-LAEA Europe (EPSG: 3035) coordinate reference system.Einwohner: The population count within each cell.

Prepare Data

df_pop.rename(columns={'Einwohner': 'Population'}, inplace=True)

df_pop['Population'] = pd.to_numeric(df_pop['Population'], errors='coerce') # coerce: any value that cannot be converted to a numeric type will be replaced with NaNTo visualize the data on a map, we need to transform the coordinates into polygons representing each grid cell. The dataset uses the ETRS89-LAEA Europe coordinate reference system, which measures distances in meters and is well-suited for European datasets.

Since each grid cell is 100m x 100m, and the coordinates provided represent the center of each cell, we can use this information - combined with the fact that the CRS measures in meters - to create accurate polygons. When creating the geopandas GeoDataFrame, we’ll ensure that the correct CRS (ETRS89-LAEA) is set. However, for visualization in lonboard, we need to convert the coordinates to the more commonly used WGS84 (EPSG:4326) CRS, which is based on latitude and longitude.

The following code will generate geopandas Polygons for each cell and convert the CRS for visualization:

def create_polygon(x, y, half_length=50):

return Polygon([

(x - half_length, y - half_length),

(x + half_length, y - half_length),

(x + half_length, y + half_length),

(x - half_length, y + half_length)

])

gdf_population = gpd.GeoDataFrame(df_pop['Population'], geometry=df_pop.apply(lambda row: create_polygon(row['x_mp_100m'], row['y_mp_100m']), axis=1), crs = 'EPSG:3035')

# Convert the coordinate system to WGS84 (EPSG:4326)

gdf_population = gdf_population.to_crs(epsg=4326)gdf_population.info()<class 'geopandas.geodataframe.GeoDataFrame'>

RangeIndex: 3088037 entries, 0 to 3088036

Data columns (total 2 columns):

# Column Dtype

--- ------ -----

0 Population int64

1 geometry geometry

dtypes: geometry(1), int64(1)

memory usage: 47.1 MB

gdf_population| Population | geometry |

| :--------- | :------------------------------------------------ |

| 4 | POLYGON ((10.21146 47.31529, 10.21278 47.31529... |

| 11 | POLYGON ((10.26565 47.31517, 10.26697 47.31517... |

| 4 | POLYGON ((10.26705 47.33047, 10.26837 47.33046... |

| 12 | POLYGON ((10.26707 47.33407, 10.26839 47.33407... |

| 3 | POLYGON ((10.26707 47.33497, 10.26839 47.33497... |

| ... | ... |

| 14 | POLYGON ((8.42288 55.02299, 8.42445 55.02301, ... |

| 4 | POLYGON ((8.41816 55.02383, 8.41972 55.02385, ... |

| 10 | POLYGON ((8.41972 55.02385, 8.42129 55.02387, ... |

| 3 | POLYGON ((8.42129 55.02387, 8.42285 55.02389, ... |

| 3 | POLYGON ((8.42285 55.02389, 8.42441 55.02391, ... |

3088037 rows × 2 columns

Visualize Data Using lonboard

To visualize the population data, we use the SolidPolygonLayer. This layer is preferred over PolygonLayer because it does not render polygon outlines, making it more performant for large datasets.

We’ll create the SolidPolygonLayer from the GeoDataFrame we generated earlier and then add it to a Map for visualization:

polygon_layer = SolidPolygonLayer.from_geopandas(

gdf_population,

)

m = Map(polygon_layer) mMap(layers=[SolidPolygonLayer(table=pyarrow.Table

Population: uint16

geometry: list<item: list<item: fixed_siz…

Set a Colormap

We can explore the documentation for SolidPolygonLayer to learn about the various rendering options it offers. Instead of using the default black fill color, let’s customize the appearance by setting a new one. Since get_fill_color is a mutable property, we can easily update the color dynamically after creating the layer, without needing to recreate it.

polygon_layer.get_fill_color = [11, 127, 171]Blue is pretty, but let’s make our map more insightful by coloring each area based on its population. Using a colormap from matplotlib, we’ll scale the population values between 0 and 1. This will allow us to easily compare different population densities at a glance.

colormap = mpl.colormaps["YlOrRd"]

normalizer = mpl.colors.Normalize(0, vmax=gdf_population['Population'].max()) #Normalize population to the 0-1 range

colors = colormap(normalizer(gdf_population['Population']), bytes=True)polygon_layer.get_fill_color = colorsThe new colorscheme already makes the map more insightful. However, it looks like the red colors aren’t showing up much, which might suggest that our data is skewed. Let’s check

def thousands_formatter(x, pos):

return f'{int(x):,}'

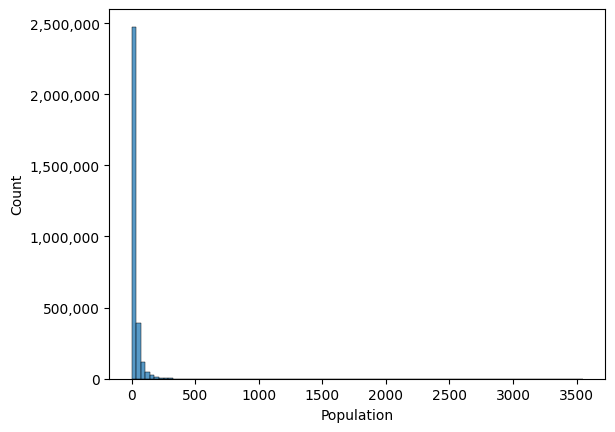

sns.histplot(gdf_population['Population'], bins=100)

plt.gca().yaxis.set_major_formatter(mticker.FuncFormatter(thousands_formatter))

plt.show()

print("Skewness value:",gdf_population['Population'].skew())

Skewness value: 4.7072006305650085

The histogram and skewness reveal a strong positive skew — most cells have low populations, while only a few cells have very high numbers. This is why our linear colormap isn’t showing much color variation. To make these differences stand out, let’s switch to a logarithmic colormap, which will better highlight the variations in population density.

normalizer = mpl.colors.LogNorm(vmin=gdf_population['Population'].min(), vmax=gdf_population['Population'].max()) # Normalize population to the 0-1 range on a log scale.

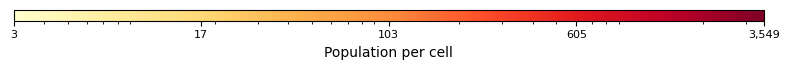

colors = colormap(normalizer(gdf_population['Population']), bytes=True)polygon_layer.get_fill_color = colorsAdd a Legend

To make our map even clearer, let’s add a colorbar that shows how population densities correspond to colors. This will help users easily interpret the map.

Here’s how we can set it up:

def create_colorbar():

fig, ax = plt.subplots(figsize=(8, 0.8))

# Define the colorbar with LogNorm and the specified colormap

cbar = plt.colorbar(

plt.cm.ScalarMappable(norm=LogNorm(vmin=gdf_population['Population'].min(), vmax=gdf_population['Population'].max()), cmap=colormap),

cax=ax,

orientation='horizontal'

)

tick_values = np.logspace(np.log10(gdf_population['Population'].min()), np.log10(gdf_population['Population'].max()), num=5)

cbar.set_ticks(tick_values)

cbar.ax.xaxis.set_major_formatter(mticker.FuncFormatter(thousands_formatter))

cbar.ax.tick_params(labelsize=8)

cbar.set_label('Population per cell', fontsize=10)

plt.tight_layout()

plt.show()

create_colorbar()

By using Jupyter widgets, we can capture the colorbar and then combine it with the map for a more comprehensive view.

# Display the map and the colorbar together

# Create output widget for the colorbar

colorbar_output = widgets.Output()

with colorbar_output:

create_colorbar()

widgets.VBox([m, colorbar_output])VBox(children=(Map(layers=[SolidPolygonLayer(get_fill_color=<pyarrow.lib.FixedSizeListArray object at 0x371fa6…

Share a Map

To share your interactive map, you can save it as an .html file. This allows others to view and interact with the map in a web browser without needing any specialized software.

Here’s a simple way to save your map as an .html file:

m.to_html("visualization_population.html")!open visualization_population.htmlBe aware that saving to .html embeds the entire dataset into the file, which can result in a large file size. This might not be the most efficient way to share large datasets.

An alternative solution is to use Shiny, which integrates with Jupyter Widgets and supports lonboard. Shiny allows you to host the map and data separately, providing a more efficient way to share interactive maps for larger datasets.

Additional Customization

Interactive Filtering

To make our map even more interactive, we can add filters that allow us to explore the data based on specific criteria. By incorporating widgets like sliders, we can dynamically adjust which data is displayed. For example, we can use a slider to filter and display only areas with populations within a certain range, offering a more focused view of the data.

Unlike the fill color, which is a mutable property that can be changed dynamically, applying filters requires the DataFilterExtension . Extensions modify the core behavior of the layer and must be set at the time of creation. Therefore, to enable filtering, we need to create a new SolidPolygonLayer with the DataFilterExtension included. Additionally, we define a filter_range that specifies the range of values to be filtered.

lonboard leverages GPU-based filtering for efficient real-time interactivity, allowing smooth performance even with large datasets.

filter_extension = DataFilterExtension()polygon_layer = SolidPolygonLayer.from_geopandas(

gdf_population,

get_fill_color = colors,

extensions=[filter_extension],

get_filter_value=gdf_population['Population'],

filter_range=[3, 3549]

)with widgets.Output():

# Create the slider

slider = widgets.IntRangeSlider(

value=(3, 25),

min=3,

max=3549,

step=1,

description="Slider: ",

layout=widgets.Layout(width='600px'),

)

# Link the slider to the polygon layer

widgets.jsdlink(

(slider, "value"),

(polygon_layer, "filter_range")

)sliderIntRangeSlider(value=(3, 25), description='Slider: ', layout=Layout(width='600px'), max=3549, min=3)

m = Map(polygon_layer)

mMap(layers=[SolidPolygonLayer(extensions=[DataFilterExtension()], filter_range=[3.0, 25.0], get_fill_color=<py…

3D Maps

To add a 3D perspective to our map, we can give the polygons height based on the population data. By setting the extruded parameter to True, we can add elevation to the polygons, making areas with higher populations rise above the map. While this feature may not be the most appropriate for this dataset, it demonstrates how 3D visualization can be useful for other types of data, such as building heights or terrain.

Just like the extensions property, extruded alters the core behavior of the layer. Therefore, we need to create a new SolidPolygonLayer with the extruded property set during its creation.

Here’s how it works:

polygon_layer = SolidPolygonLayer.from_geopandas(

gdf_population,

get_fill_color= colors,

extruded = True

)polygon_layer.get_elevation = 1500 * normalizer(gdf_population['Population'])m = Map(polygon_layer)

mMap(layers=[SolidPolygonLayer(extruded=True, get_elevation=<pyarrow.lib.FloatArray object at 0x387493160>

[

…

Summary

In this notebook, we explored how to visualize large spatial datasets, specifically Germany’s population data, using the lonboard library. You’ve seen how to fetch, clean, and transform population data into polygons, apply color scales to represent population density, and use advanced features like interactive filters and 3D maps for richer insights.

By now, you should have a better understanding of how to handle and visualize large datasets directly in Jupyter notebooks, as well as how to customize maps for more meaningful visual representation.

Learn More: If you’d like to explore further, check out the lonboard documentation for more advanced functionalities.